Countless Discoveries and Rediscoveries: British Women Artists at Tate Britain

Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520–1920 exceeds the promise of its title: it brings out of the shadows (and storerooms!) works by more than one hundred women artists who have been historically hidden from public view. Curated by Tabitha Barber and Tim Batchelor, the exhibition, open at Tate Britain until 13 October 2024, integrates works from the Tate’s holdings with loans from public and private collections. It is an undeniably impressive show, ambitious in its aim to trace a history of British art exclusively by women. Along with other recent exhibitions such as Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800, and Women Masters, Now You See Us is an important reminder that many women artists still remain on the margins of our understanding of art history.

The exhibition unfolds in a loose chronology, ranging from Tudor-era miniatures to Modern British painting. Within this broad chronological framework, the show and catalogue are organized around thematic clusters that prompt an exploration of certain subject matter or media that women particularly excelled at, such as flower painting or watercolour. Institutional obstacles are also dealt with thematically, with sections like The First Professionals and Art School.[1] Better-known works by artists such Angelica Kauffman, Julia Margaret Cameron, and Vanessa Bell are interspersed with less familiar but equally compelling works, such as Mary Beale’s Self-portrait as Artemisia (c. 1675; Fig. 1), Louise Jopling’s Through the Looking-Glass (1875; Fig. 2) recently acquired by Tate Britain, or the intricate The Deceitfulness of Riches (1901) by Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, a Neo-Pre-Raphaelite.

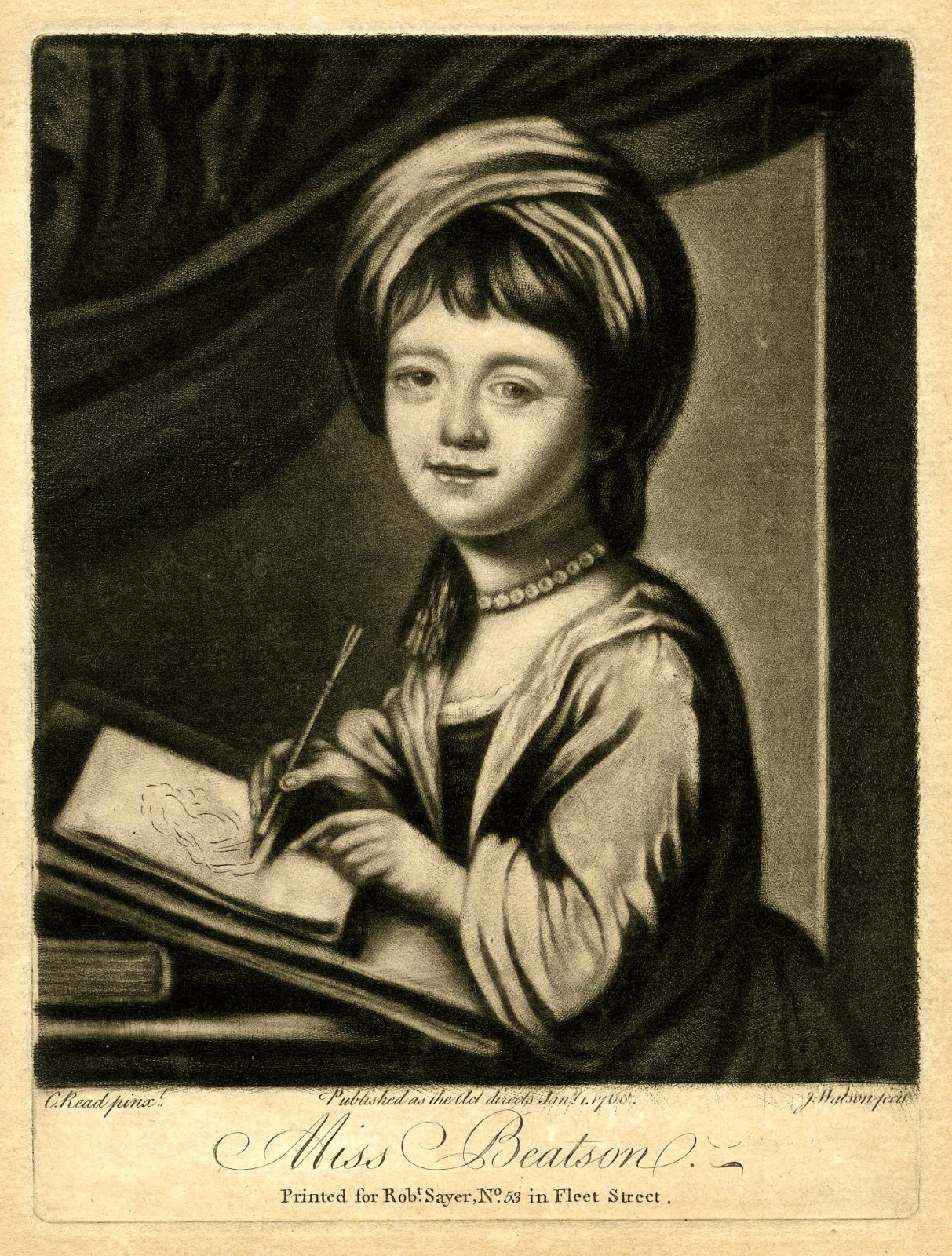

Miss Helena Beatson, a pastel by Katherine Read (1723–1778), is on loan to the exhibition from the Katrin Bellinger Collection (Fig. 3). Seven additional portraits by Read appear in the show—three in pastel and four in oil—which comprises a substantial portion of the eighteenth-century works presented. Read was born in Scotland in 1723 and trained in Paris and Rome with Maurice-Quentin de La Tour before establishing her London studio.[2] Unlike many of the artists that Now You See Us introduces, Read did not come from an artistic family. She found an initial clientele for her portraits through her family’s Jacobite contacts, which she subsequently built upon as her reputation grew. She exhibited at many of the most coveted venues, including the Royal Academy, the Free Society, and the Society of Artists, and was commercially successful.

Read may have been inspired to work in pastel as well as oil because of her training with La Tour, who was a celebrated pastelist. However, pastel was also a more accepted medium for women artists: it was associated with contemporary stereotypes of femininity because of its softness and delicacy. Like watercolor and needlework, pastel was considered a less “serious” medium than oil, despite its immense popularity among eighteenth-century collectors. This meant that women artists working in these media could more easily avoid vehement criticism while achieving commercial success. Read’s technical handling in Miss Helena Beatson is exquisite; she creates soft and blended passages in her subject’s hair, skin, and fabric, while retaining a detailed sharpness in the necklace, pen and drawing.

The portrait also exacerbates an unanticipated—and joyful—theme that emerges from the exhibition. In the face of countless challenges, both institutional and social, women artists regularly forged support networks with each other and with their patrons. For example, Read met the renowned Italian artist Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757) on a visit to Venice in 1753, and the two discussed pastel techniques.[3] Miss Helena Beatsonis a depiction of Read’s orphaned niece: five years old at the time of sitting, Beatson was considered a child prodigy.[4] The portrait shows the young sitter in the act of drawing a mother and child; it may be an art lesson, as Read taught Beatson. Unlike Read, Beatson chose not to pursue art as a profession, and halted her practice when she reached adulthood. Nevertheless, Read left much of her money to her female nieces in the hopes of providing them with financial independence.[5] Such indications of friendship and artistic collaboration provide an antidote to the many stories of gendered prejudice that appear elsewhere in the show.

While Katherine Read fell into obscurity after her death, she was well known in her own time. Her popularity is evidenced by the circulation of a mezzotint print after her pastel (Fig. 4), an impression of which is also in the Katrin Bellinger Collection. James Watson’s printed version of Miss Helena Beatson would have provided buyers with a more affordable version of the image and suggests that it reached a wider audience. This points to another leitmotif that recurs throughout the exhibition: that of the culpability of historians, critics, and art institutions in the dismissal of women artists and their subsequent need for “rediscovery” today. Reattributions abound in the show; most notably, perhaps, in the case of Artemisia Gentileschi’s Susanna and the Elders, which was catalogued as “French School” until 2023 (Fig. 5).[6] Read’s work has also been frequently misattributed to her male contemporaries, including Jean-Etienne Liotard, Joshua Reynolds, and Anton Raphael Mengs.[7] Such moments of rediscovery highlight the continued importance of organizing exhibitions devoted to women artists, even decades after the rise of feminist art history.

The Artist at Work collection holds significant potential for ongoing research into women artists in Britain and beyond. It is often through portraits or studio scenes that a particular woman’s artistic practice can be uncovered, especially if they did not sell their art or exhibit publicly under their own name. Such images also expose the artistic and personal networks through which women artists were able to thrive and situates them accurately in their historical contexts. Many of these works can now be explored together on the website under the theme “Women Artists.” In this context it is also worth mentioning the website of AWARE (Archives for Women Artists Research and Exhibitions), which offers a freely accessible and ever increasing wealth of research on women artists’ biographies, both historical and contemporary.

The exhibition catalogue is also available from Tate’s website.

Notes

[1] Tabitha Barber and Tim Batchelor, eds., Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 (London: Tate Publishing, 2024).

[2] For more on Read, see: Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, online edition, http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/Read.pdf#search=%22read%22

[3] Barber and Batchelor, Now You See Us, 85.

[4] See Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, online edition, http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/Beatson.pdf

[5] Barber and Batchelor, Now You See Us, 56.

[6] Barber and Batchelor, 27.

[7] Barber and Batchelor, 56.

Fig. 1: Mary Beale, Self-portrait as Artemisia, c. 1675, oil on sacking. West Suffolk Heritage Service.

Fig. 2: Louise Jopling, Through the Looking-Glass, 1875, oil on canvas. Tate.

Fig. 3: Katherine Read, Miss Helena Beatson, 1767, pastel. Katrin Bellinger Collection.

Fig. 4: James Watson, Miss Helena Beatson, 1768, mezzotint. The British Museum.

Fig. 5: Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Elders, c.1638-40, oil on canvas. Royal Collection Trust.