Pre-Raphaelite Sisters at the National Portrait Gallery

After supporting the successful exhibition The Encounter: Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt in 2017, the Tavolozza Foundation was happy to contribute once again to one of the National Portrait Gallery’s thoroughly researched and insightful shows, Pre-Raphaelite Sisters.

Curated by Jan Marsh, the premise for the exhibition is to give space and voice to some of the women who ‘were vitally engaged in creating Pre-Raphaelite art’ [1]. The show and the catalogue (which includes essays by Peter Funnell, Charlotte Gere, Pamela Gerrish Nunn, and Alison Smith) focus on the creative contribution of twelve women, whose role as partners, wives, models, artists and poets has long been overlooked.

Although not solely concerned with the role of women as artists in relation to the activities of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood (1850-1900), the show highlights the careers and achievements of several female artists. Iconic works are presented side by side with little-known pieces, with each protagonist being devoted a distinct section.

Upon entering the first room, devoted to Effie Gray Millais (1828-1897), I was instantly met with some familiar faces. The display includes three humorous drawings by John Everett Millais that once belonged to the same album as one in the Katrin Bellinger collection (fig. 1) [2]. Effie’s first husband, John Ruskin, was an early supporter of the Pre-Raphaelites, defending them against the attacks of the critics, who saw their art as offensive and absurd.

The sketches record Millais’s and Effie Ruskin’s time spent together in Brig o’Turk in Stirlingshire, Scotland, in 1853. Millais and his brother William had joined the couple, with the pretext that while Ruskin worked on his writing, Millais would paint the background for a portrait of him. In reality, the stay turned into an opportunity for Millais and Effie Ruskin to get closer and the ‘Highland Sketchbooks’ scenes betray their increasing intimacy. The inscription on our sheet, ‘Two Masters and their Pupils’, ironically refers to the fact that Millais was Effie’s drawing-master while John Ruskin, whose figure has been cut away from the upper right corner, was teaching Millais the principles of architecture. Only two years later, Effie and Millais were married. As well as modelling for Millais, she became his invaluable assistant, researcher, and business partner, contributing to his success. She was also a talented watercolourist and some of drawings are included in the display.

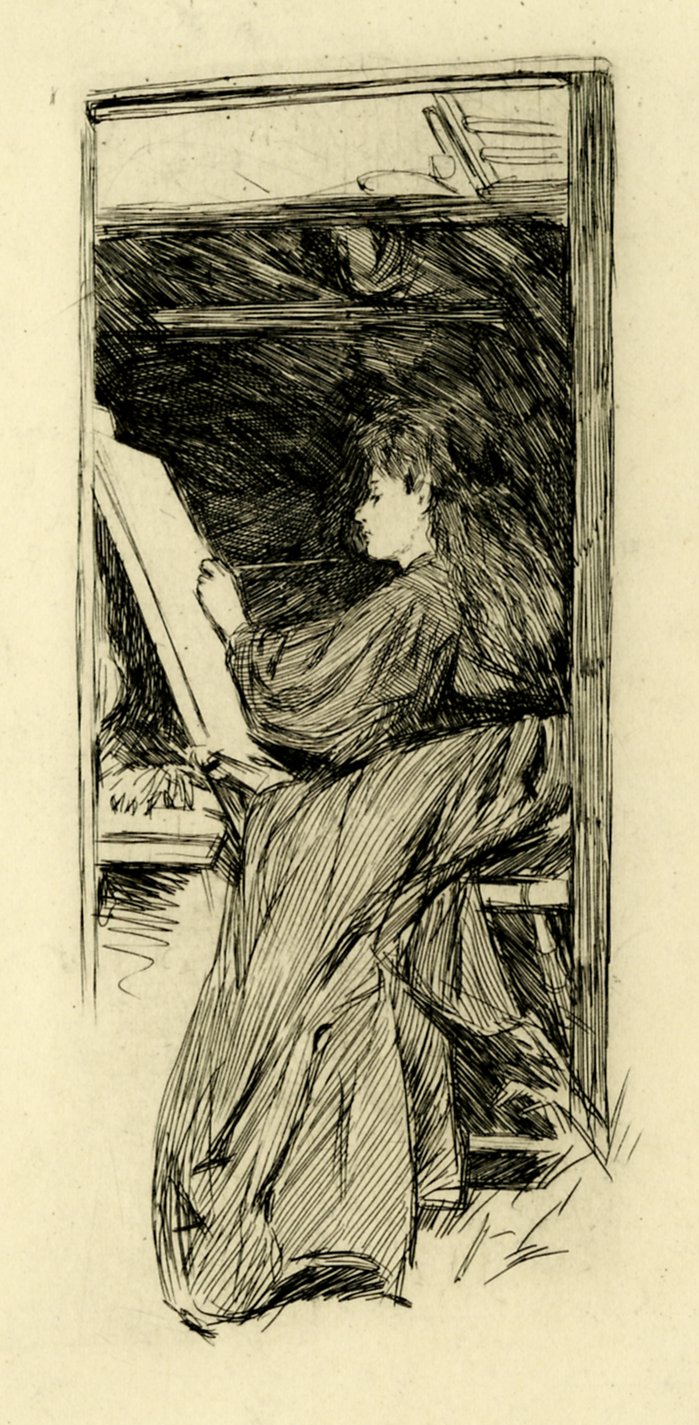

Another artist whose personal and professional life became closely intertwined with the Brotherhood was Maria Zambaco (1843-1914), whose considerable artistic output is sadly largely lost today. She is known as the model and lover of Edward Burne-Jones, with whom she had a long, tormented affair. Her charm is vividly captured in a small etching by Charles Keene showing Zambaco drawing (fig. 2). In its graphic language and narrow vertical format, it reminded me of a piece in the Katrin Bellinger collection: Keene’s pen and ink drawing of a young woman standing by an easel, holding palette and mahl-stick (fig. 3). With its controlled handling of the pen and pared-down composition, our drawing is a typical example of Keene’s draughtsmanship. The young woman posing by an easel is Dorothea Corbould (1849-1928), one of the daughters of painter Alfred Corbould and of Mary Keene, the artist’s sister [3].

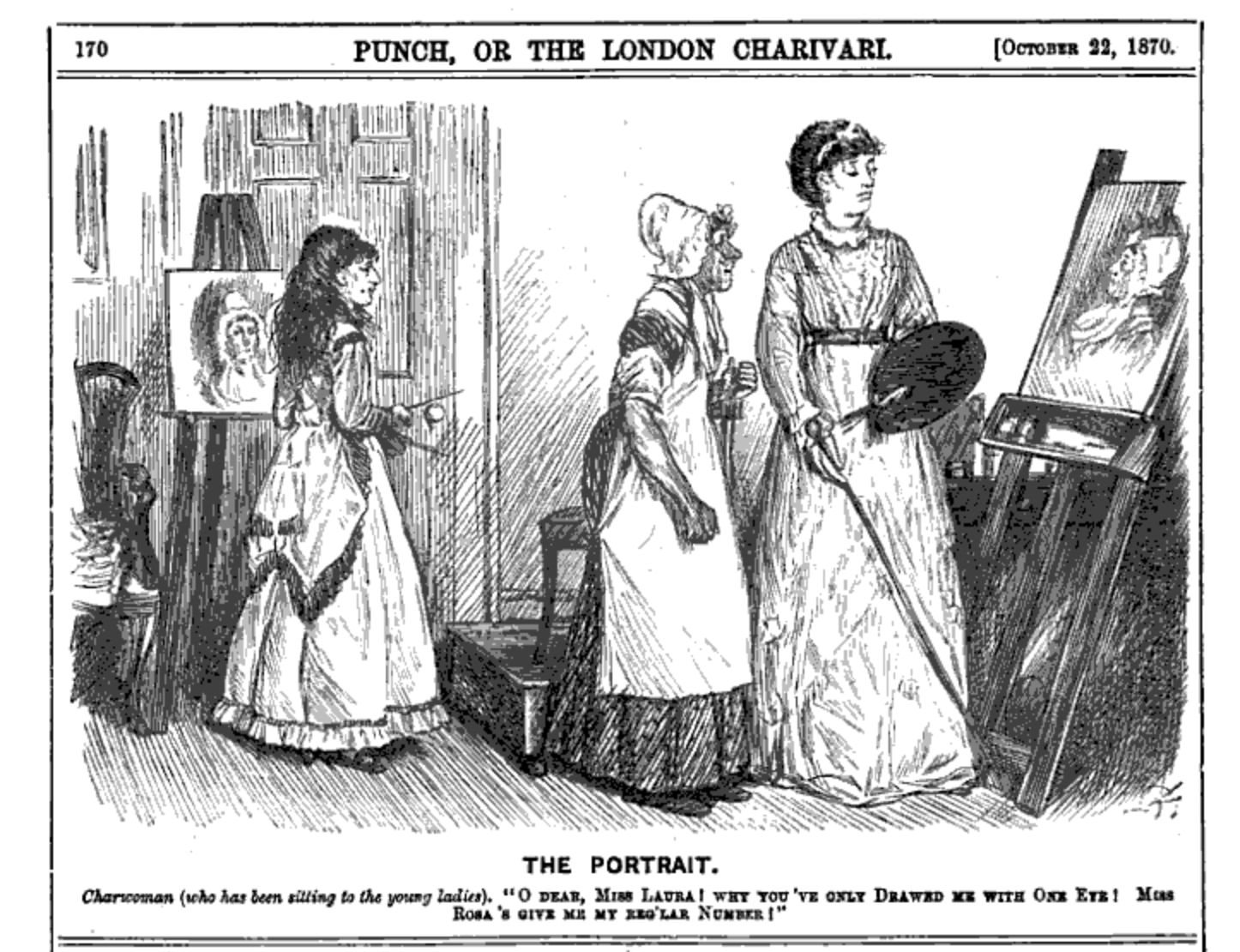

Charles Keene’s penchant for depicting artists at work earned him the moniker of ‘artists’ artist’. He also made a large number of sketches of his friends and family as is the case with our drawing portraying his niece Dorothea. That he would later include the young woman with a palette and brush in one of his cartoons for Punch adds to the appeal of this intimate sketch. [4] The cartoon, entitled The Portrait (fig. 4), pokes fun at visual literacy and artistic sophistication, touching on issues of gender and class in Keene’s distinctive subtle humour. Not a lot is known about Dorothea and we cannot be sure whether she painted, but we know that she had an artistic soul – her novel Loyal Hearts was published in 1883.

Pre-Raphaelite Sisters is open at the National Portrait Gallery until 26 January 2020

Notes:

[1] Jan Marsh, with contributions by Peter Funnell, Charlotte Gere, Pamela Gerrish Nunn, and Alison Smith, Pre-Raphaelite Sisters, exhibition catalogue, National Portrait Gallery, London, 2019, p. 8.

[2] Marsh, Pre-Raphaelite Sisters, pp. 51-52, figs. 32-34.

[3] A portrait of the young Dorothea Corbould, reading, c. 1860, is at Tate, inv. No. T02082

[4] Punch, or the London Charivari, vol. 59, October 22, 1870, p. 170: Charwoman (who has been sitting to the young ladies). “O dear, Miss Laura! Why you’ve only drawed me with one eye! Miss Rosa’s give me my regular number!”

Fig. 1 John Everett Millais, Two Masters and their Pupils, 1853, pen and ink, 184 x 236 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection

Fig. 2 Charles Keene, Madame Zambaco Drawing, 1869-70, etching, 163 x 105 mm, British Museum, London, inv. no. 1892,0514.49

Fig. 3 Charles Keene, A Woman Artist by her Easel (Dorothea Corbould), pen and ink, 204 x 100 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection

Fig. 4 The Portrait, in Punch, or the London Charivari, vol. 59, October 22, 1870, p. 170